Macchi C.200 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Macchi C.200 Saetta (Italian: "Lightning"), or MC.200, was a

In August 1939, about 30 C.200 Saettas were delivered to the 10th ''Gruppo'' of the 4th ''Stormo'', stationed in North Africa. However, pilots of this elite unit of the

In August 1939, about 30 C.200 Saettas were delivered to the 10th ''Gruppo'' of the 4th ''Stormo'', stationed in North Africa. However, pilots of this elite unit of the

In September 1940, the C.200s of the 6th Gruppo conducted their first offensive operations in support of wider

In September 1940, the C.200s of the 6th Gruppo conducted their first offensive operations in support of wider

C.200s from the 4th ''Stormo'' took part in operations against Yugoslavia right from the start of hostilities.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 6–7. At dawn on 6 April 1941, four C.200s from 73a ''Squadriglia'' flew over

C.200s from the 4th ''Stormo'' took part in operations against Yugoslavia right from the start of hostilities.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 6–7. At dawn on 6 April 1941, four C.200s from 73a ''Squadriglia'' flew over

During April 1941, the C.200s of the 374th ''Squadriglia'' became the first unit to be stationed on the North African mainland. Further units, including the 153rd ''Gruppo'' and the 157th ''Gruppo'', were stationed on the mainland as Allied air power in the region increased in capability and numbers, including aircraft such as the Hurricane and the

During April 1941, the C.200s of the 374th ''Squadriglia'' became the first unit to be stationed on the North African mainland. Further units, including the 153rd ''Gruppo'' and the 157th ''Gruppo'', were stationed on the mainland as Allied air power in the region increased in capability and numbers, including aircraft such as the Hurricane and the  In addition to interceptor duties, C.200s frequently operated as fighter-bombers against both land and naval objectives. The North African theatre was the first in which the type had been intentionally deployed as a fighter-bomber.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 7–8. During September 1942, the type was responsible for sinking the British destroyer , as well as several smaller motor vessels, near

In addition to interceptor duties, C.200s frequently operated as fighter-bombers against both land and naval objectives. The North African theatre was the first in which the type had been intentionally deployed as a fighter-bomber.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 7–8. During September 1942, the type was responsible for sinking the British destroyer , as well as several smaller motor vessels, near

fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

developed and manufactured by Aeronautica Macchi

Aermacchi was an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Formerly known as Aeronautica Macchi, the company was founded in 1912 by Giulio Macchi at Varese in north-western Lombardy as Nieuport-Macchi, to build Nieuport monoplanes under licence for the It ...

in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. Various versions were flown by the ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was abolis ...

'' (Italian Air Force) who used the type throughout the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The C.200 was designed by Mario Castoldi

Mario Castoldi (February 26, 1888 - May 31, 1968) was an Italian aircraft engineer and designer.

Biography

Born in Zibido San Giacomo (province of Milan), Castoldi worked for the experimental center of Italian Military Aviation at Montecelio, no ...

, Macchi's lead designer, to serve as a modern monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing confi ...

fighter aircraft, furnished with retractable landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for takeoff or landing. For aircraft it is generally needed for both. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, such as the Glenn L. Martin ...

and powered by a radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating type internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. It resembles a stylized star when viewed from the front, and is ca ...

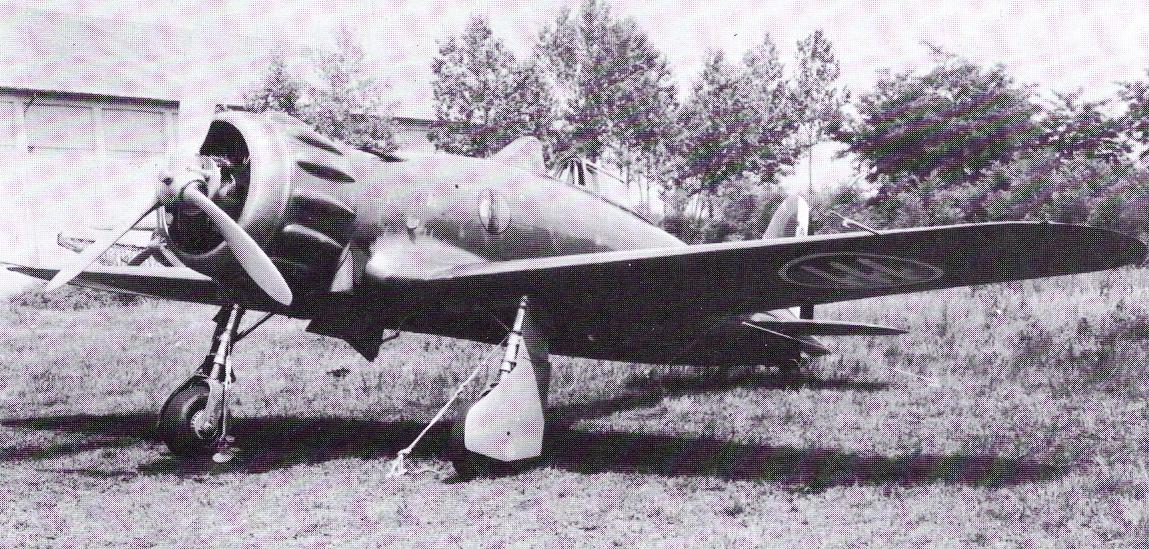

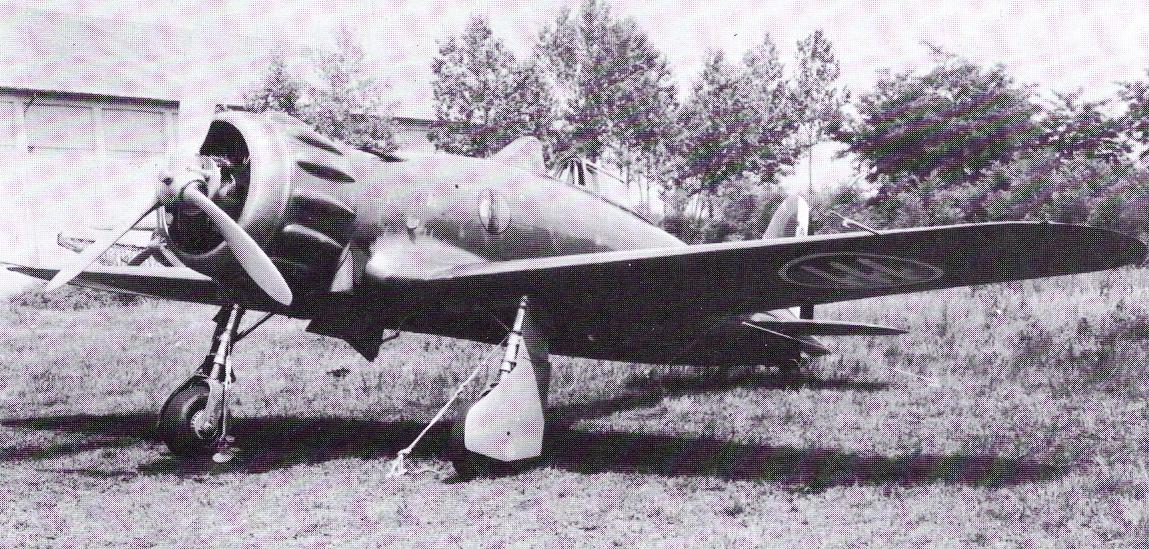

. The C.200 possessed excellent maneuverability, and its general flying characteristics left little to be desired.Munson 1960, p. 34. Its stability in a high-speed dive was exceptional,Spick 1997, p. 116. but it was underpowered and underarmed in comparison to its contemporaries.Ethell 1995, p. 68. Early on, there were a number of crashes caused by stability problems, nearly resulting in the grounding of the type; these problems were ultimately addressed via aerodynamic modifications to the wing.

From the time Italy entered the Second World War on 10 June 1940, until the signing of the armistice of 8 September 1943, the C. 200 flew more operational sorties than any other Italian aircraft. The ''Saetta'' saw operational service in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, across the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

, and in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

(where it obtained an excellent kill to loss ratio of 88 to 15).De Marchi and Tonizzo 1994, p. 10.Ethell 1995, p. 70. The plane's very strong all-metal construction and air-cooled engine made the aircraft ideal for conducting ground attack missions; several units flew it as a fighter-bomber. Over 1,000 aircraft had been constructed by the end of the war.Ethell 1995, p. 69.

Development

Origins

In early 1935Mario Castoldi

Mario Castoldi (February 26, 1888 - May 31, 1968) was an Italian aircraft engineer and designer.

Biography

Born in Zibido San Giacomo (province of Milan), Castoldi worked for the experimental center of Italian Military Aviation at Montecelio, no ...

, lead designer of Italian aircraft company Macchi, commenced work on a series of design studies for a modern monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing confi ...

fighter aircraft, which was to be furnished with retractable landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for takeoff or landing. For aircraft it is generally needed for both. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, such as the Glenn L. Martin ...

.Cattaneo 1966, p. 3. Castoldi had previously designed several racing aircraft that had competed for the Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded annually (and later, biennially) to the winner of a race for seaplanes and flying ...

, including the Macchi M.39

The Macchi M.39 was a racing seaplane designed and built by the Italian aircraft company Aeronautica Macchi in 1925–26. An M.39 piloted by Major Mario de Bernardi (1893–1959) won the 1926 Schneider Trophy, and the type also set world speed ...

, which won the competition in 1926. He had also designed the M.C. 72. From an early stage, the concept aircraft that emerged from these studies became known as the ''C.200''.

In 1936, in the aftermath of Italy's campaigns in East Africa, an official program was initiated with the aim of completely re-equipping the ''Regia Aeronautica'' with a new interceptor aircraft

An interceptor aircraft, or simply interceptor, is a type of fighter aircraft designed specifically for the defensive interception role against an attacking enemy aircraft, particularly bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Aircraft that are cap ...

of modern design. The 10 February 1936 specifications, formulated and published by the ''Ministero dell'Aeronatica'', called for an aircraft powered by a single radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating type internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. It resembles a stylized star when viewed from the front, and is ca ...

, which was to be capable of a top speed of and a climb rate of 6,000 meters in 5 minutes. Additional requirements were soon specified: the aircraft was to be capable of being used as an interceptor with a flight endurance time of two hours and armed with a single (later increased to two) machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

.

Prototypes

In response to the prescribed demand for a modern fighter aircraft, Castoldi submitted a proposal for an aircraft based upon his 1935 design studies. On 24 December 1937, the firstprototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and Software prototyping, software programming. A prototyp ...

(MM.336) C.200 conducted its maiden flight

The maiden flight, also known as first flight, of an aircraft is the first occasion on which it leaves the ground under its own power. The same term is also used for the first launch of rockets.

The maiden flight of a new aircraft type is alwa ...

at Lonate Pozzolo

Lonate Pozzolo is a town and ''comune'' located in the province of Varese, in the Lombardy region of northern Italy. It is served by Ferno-Lonate Pozzolo railway station.

The airline Cargoitalia

Cargoitalia S.p.A. was a cargo airline with its ...

, Varese

Varese ( , , or ; lmo, label= Varesino, Varés ; la, Baretium; archaic german: Väris) is a city and ''comune'' in north-western Lombardy, northern Italy, north-west of Milan. The population of Varese in 2018 has reached 80,559.

It is the c ...

, with Macchi chief test pilot Giuseppe Burei

Giuseppe is the Italian form of the given name Joseph,

from Latin Iōsēphus from Ancient Greek Ἰωσήφ (Iōsḗph), from Hebrew יוסף.

It is the most common name in Italy and is unique (97%) to it.

The feminine form of the name is Giusep ...

at the controls. Officials within the ministry and Macchi's design team fought over the retention of the characteristic hump used to enhance cockpit visibility; after a protracted argument, the feature was ultimately retained.

The first prototype was followed by the second prototype early the following year. During testing, the aircraft reportedly attained in a dive free of negative tendencies such as flutter and other aeroelastic issues; although it could achieve only in level flight due to a lack of engine power. Nevertheless, this capability was superior than the performance of the competing Fiat G.50 Freccia

The Fiat G.50 ''Freccia'' ("Arrow") was a World War II Italian fighter aircraft developed and manufactured by aviation company Fiat. Upon entering service, the type became Italy’s first single-seat, all-metal monoplane that had an enclosed co ...

, Reggiane Re.2000

The Reggiane Re.2000 ''Falco'' I was an Italian all metal, low-wing monoplane developed and manufactured by aircraft company Reggiane. The type was used by the ''Regia Aeronautica'' (Italian Air Force) and the Swedish Air Force during the first p ...

, A.U.T. 18, IMAM Ro.51

The IMAM Ro.51 was an Italian fighter aircraft that first flew in 1937. It was designed for the 1936 new fighter contest for the Regia Aeronautica, with practically all the Italian aircraft builders involved.

Design

The aircraft, designed by th ...

, and Caproni-Vizzola F.5

The Caproni Vizzola F.5 was an Italian fighter aircraft that was built by Caproni. It was a single-seat, low-wing cantilever monoplane with retractable landing gear.

Development

The F.5 was developed in parallel with the Caproni Vizzola F.4, w ...

; of these, the Re.2000 was seen as the most capable of the C.200's rivals, being more maneuverable and capable of greater performance at low altitude but lacking in structural strength.

The C.200 benefitted greatly from preparations that were being made for major expansion of the Italian Air Force, known as Programme R. In 1938, the C.200 was selected as the winner of the tender "Caccia I" (Fighter 1) of the ''Regia Aeronautica''. This choice came in spite of mixed results during flight testing at Guidonia airport

Guidonia Air Base ( it, Aeroporto di Guidonia, ICAO: LIRG) is a military airport in Guidonia Montecelio, Province of Rome, near Rome. It is home to the Italian Air Force's main logistic center.

History

The airport was built between 1915 and 1 ...

; on 11 June 1938, Major Ugo Borgogno warned that when tight turns at beyond 90° were attempted, the aircraft became extremely difficult to control, including a tendency to turn upside down, mostly to the right and entering into a violent flat spin.de Marchi 1994,

Production

Shortly following the completion of the second prototype, an initial order for 99 production aircraft was placed with Macchi. The G.50, which during the same flight tests held at Guidonia airport had out-turned the Macchi, was also placed in limited production, because it had been determined that the former could be brought into service earlier. The decision, or indecision, involved in producing multiple overlapping types led to greater inefficiencies in both production and in operation.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 3–4. In June 1939, production of the C.200 formally commenced. The most serious handicap was the low production rate of the type. According to some reports, in excess of 22,000 hours in production time was attributed to the use of antiquated construction technology. A lack of urgency shown by the authorities regarding standardisation was also viewed as having negatively affected mass production efforts, particularly in light of the lack of availability of key resources in Italy at the time. In order to improve the rate of output, the C.200 remained almost unchanged throughout its production life, save for adjustments to the cockpit in response to pilot feedback. In addition to Macchi, the C.200 was also constructed by Italian aircraft companiesSocietà Italiana Ernesto Breda

Società Italiana Ernesto Breda (), more usually referred to simply as Breda, was an Italian mechanical manufacturing company founded by Ernesto Breda in Milan in 1886.

History

The firm was founded by Ernesto Breda in Milan in 1886. It original ...

and SAI Ambrosini

__NOTOC__

SAI Ambrosini was an Italian aircraft manufacturer established in Passignano sul Trasimeno, Italy, in 1922 as the ''Società Aeronautica Italiana''. It became SAI Ambrosini when it was acquired by the Ambrosini group in 1934. Prior to ...

under a subcontracting

A subcontractor is an individual or (in many cases) a business that signs a contract to perform part or all of the obligations of another's contract.

Put simply the role of a subcontractor is to execute the job they are hired by the contractor ...

arrangement intended to produce 1,200 aircraft between 1939 and 1943.Cattaneo 1966, p. 5. However, during 1940, the termination of all production of the type was considered in response to aerodynamic performance problems that had caused the loss of multiple aircraft; the type was retained after changes were made to the wing to rectify a tendency to go into an uncontrollable spin that could occur during turns.

In an attempt to improve performance, a C.201 prototype was created with a Fiat A.76 engine; work on this prototype was later abandoned in favour of the Daimler-Benz DB 601

The Daimler-Benz DB 601 was a German aircraft engine built during World War II. It was a liquid-cooled inverted V12 engine, V12, and powered the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Bf 110, and many others. Approximately 19,000 601's were pr ...

-powered C.202. At one point, it was intended that the ''Saetta'' was to have been replaced outright by the C.202 after only a single year in production. However, the C.200's service life was extended because Alfa Romeo

Alfa Romeo Automobiles S.p.A. () is an Italian luxury car manufacturer and a subsidiary of Stellantis. The company was founded on 24 June 1910, in Milan, Italy. "Alfa" is an acronym of its founding name, "Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili." ...

proved to be incapable of producing enough of the RA.1000 (license-built DB 601) engines needed by the newer aircraft. This contributed to the decision to construct further C.200s that used C.202 components as an interim measure while waiting for the production rate of the latter's engine to be increased.

At the beginning of 1940, Denmark was set to place an order for 12 C.200s to replace its aging Hawker Nimrod

The Hawker Nimrod is a British carrier-based single-engine, single-seat biplane fighter aircraft built in the early 1930s by Hawker Aircraft.

Design and development

In 1926 the Air Ministry specification N.21/26 was intended to produce a suc ...

fighters, but the deal fell through when Germany invaded Denmark. A total of 1,153 ''Saettas'' were eventually produced, but only 33 remained operational by the time armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brigad ...

in September 1943.

Design

The Macchi C.200 was a modern all-metalcantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is supported at only one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a canti ...

low-wing monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing confi ...

, which was equipped with retractable landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for takeoff or landing. For aircraft it is generally needed for both. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, such as the Glenn L. Martin ...

and an enclosed cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, usually near the front of an aircraft or spacecraft, from which a Pilot in command, pilot controls the aircraft.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the ...

. The fuselage was of semi-monocoque

Monocoque ( ), also called structural skin, is a structural system in which loads are supported by an object's external skin, in a manner similar to an egg shell. The word ''monocoque'' is a French term for "single shell".

First used for boats, ...

construction, with self-sealing fuel tank

A self-sealing fuel tank is a type of fuel tank, typically used in aircraft fuel tanks or fuel bladders, that prevents them from leaking fuel and igniting after being damaged.

Typical self-sealing tanks have multiple layers of rubber and reinforc ...

s under the pilot's seat, and in the centre section of the wing. The distinctive "hump" elevated the partially open cockpit to provide the pilot with an unusually wide field of view over the engine. The wing had an advanced system whereby the hydraulic

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counter ...

ally actuated flap

Flap may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Flap'' (film), a 1970 American film

* Flap, a boss character in the arcade game ''Gaiapolis''

* Flap, a minor character in the film '' Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland''

Biology and he ...

s were interconnected with the aileron

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement around ...

s, so that when the flaps were lowered the ailerons drooped as well.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 4–5. As a result of its ultimate load factor of 15.1, it could reach speeds as fast as true airspeed

The true airspeed (TAS; also KTAS, for ''knots true airspeed'') of an aircraft is the speed of the aircraft relative to the air mass through which it is flying. The true airspeed is important information for accurate navigation of an aircraft. Tr ...

during dives.Palermo 2014, p. 236.

Power was provided by a Fiat A.74

The Fiat A.74 was a two-row, fourteen-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine produced in Italy in the 1930s as a powerplant for aircraft. It was used in some of Italy's most important aircraft of World War II.

Design and development

The A.74 marked ...

radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating type internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. It resembles a stylized star when viewed from the front, and is ca ...

, although Castoldi preferred inline engines, and had used them to power all of his previous designs. Under a ''direttiva'' (air ministry specification) of 1932, Italian industrial leaders had been instructed to concentrate solely on radial engines for fighters, due to their superior reliability. The A.74 was a re-design of the American Pratt & Whitney R-1830 SC-4 Twin Wasp by engineers Tranquillo Zerbi

Tranquillo Zerbi (1891-1939) was a leading Italian automotive engineer.

Early years

Zerbi attended primary school in Pisa before being relocated to Winterthur in Switzerland, and then moving again to The Grand Duchy of Baden which at this point ...

and , and was the only Italian-built engine that could provide a level of reliability comparable to Allied designs.Cattaneo 1966, p. 4. The licence-built A.74 engine could be problematic. In late spring 1941, 4o Stormo's Macchi C.200s, then based in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, had all the A.74s produced by the Reggiane

Officine Meccaniche Reggiane SpA (commonly referred to as ''Reggiane'') was an Italian industrial manufacturer and aviation company.

Reggiane was founded during 1904 by its parent company Caproni, which was in turn owned by the aeronautical eng ...

factory replaced because they were defective. The elite unit had to abort many missions against Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

due to engine problems.Duma 2007, pp. 200–201. While some considered the Macchi C.200 to have been underpowered, the air-cooled radial engine provided some pilot protection during strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

missions. Consequently, the C.200 was often used as a ''cacciabombardiere'' (fighter-bomber

A fighter-bomber is a fighter aircraft that has been modified, or used primarily, as a light bomber or attack aircraft. It differs from bomber and attack aircraft primarily in its origins, as a fighter that has been adapted into other roles, wh ...

).

The C.200 was typically armed with a pair of Breda-SAFAT machine gun

Breda-SAFAT (''Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche / Breda Meccanica Bresciana'' - ''Società Anonima Fabbrica Armi Torino'') was an Italian weapons manufacturer of the 1930s and 1940s that designed and produced a range of m ...

s; while these were often considered to be insufficient, the ''Saetta'' was able to compete with contemporary Allied fighters. According to aviation author Gianni Cattaneo, perhaps the greatest weakness of the C.200 was its light machine gun armament.Cattaneo 1968, Moreover, a radio was not fitted as standard.

Like other early Italian monoplanes, the C.200 suffered from a dangerous tendency to go into a spin. Early production C.200 aircraft showed autorotation

Autorotation is a state of flight in which the main rotor system of a helicopter or other rotary-wing aircraft turns by the action of air moving up through the rotor, as with an autogyro, rather than engine power driving the rotor. Bensen, Igor ...

problems similar to those found in the Fiat G.50 Freccia

The Fiat G.50 ''Freccia'' ("Arrow") was a World War II Italian fighter aircraft developed and manufactured by aviation company Fiat. Upon entering service, the type became Italy’s first single-seat, all-metal monoplane that had an enclosed co ...

, IMAM Ro.51

The IMAM Ro.51 was an Italian fighter aircraft that first flew in 1937. It was designed for the 1936 new fighter contest for the Regia Aeronautica, with practically all the Italian aircraft builders involved.

Design

The aircraft, designed by th ...

, and the AUT 18. At the beginning of 1940, a pair of deadly accidents occurred due to autorotation. Aircraft production and deliveries were halted while the ''Regia Aeronautica'' evaluated the potential for abandoning use of the type, as the skill involved in flying the C.200 was considered to be beyond that of the average pilot. The problem was a product of the profile of the wing. Castoldi soon tested a new profile, but a solution to the autorotation problem was found by Sergio Stefanutti, chief designer of SAI Ambrosini

__NOTOC__

SAI Ambrosini was an Italian aircraft manufacturer established in Passignano sul Trasimeno, Italy, in 1922 as the ''Società Aeronautica Italiana''. It became SAI Ambrosini when it was acquired by the Ambrosini group in 1934. Prior to ...

in Passignano sul Trasimeno

Passignano sul Trasimeno is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Perugia in the Italian region of Umbria, located about 20 km northwest of Perugia.

Passignano was home to a historic Italian airplane factory, the SAI Ambrosini, now ...

, based on studies conducted by German aircraft engineer Willy Messerschmitt

Wilhelm Emil "Willy" Messerschmitt (; 26 June 1898 – 15 September 1978) was a German aircraft designer and manufacturer. In 1934, in collaboration with Walter Rethel, he designed the Messerschmitt Bf 109, which became the most importan ...

and the American National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its assets ...

(NACA). He redesigned the wing section with a variable, instead of constant, profile, which was achieved by covering parts of the wings with plywood.

The new wing entered production in 1939–1940 at SAI Ambrosini and became standard on the aircraft manufactured by Aermacchi and Breda, a licensed manufacturer. After the modified wing of the ''Saetta'' was introduced, the C.200 proved to be, for a time, the foremost Italian fighter. The first production C.200 series, did not have armour fitted to protect the pilots, as a weight-saving measure. Armour plating was incorporated when frontline units were going to replace the ''Saettas'' with the new Macchi C.202

The Macchi C.202 ''Folgore'' (Italian "thunderbolt") was an Italian fighter aircraft developed and manufactured by Macchi Aeronautica. It was operated mainly by the '' Regia Aeronautica'' (''RA''; Royal (Italian) Air Force) in and around the S ...

''Folgore'' (Thunderbolt) but in only a limited number of aircraft. After the armour was fitted, the aircraft could become difficult to fly. During aerobatic maneuvers, one could enter an extremely difficult-to-control flat spin, which would force the pilot to bail out. On 22 July 1941, Leonardo Ferrulli, one of the top-scoring ''Regia Aeronautica'' pilots, encountered the problem and was forced to bail out over Sicily.Duma 2007, p. 201.

Operational history

Introduction

In August 1939, about 30 C.200 Saettas were delivered to the 10th ''Gruppo'' of the 4th ''Stormo'', stationed in North Africa. However, pilots of this elite unit of the

In August 1939, about 30 C.200 Saettas were delivered to the 10th ''Gruppo'' of the 4th ''Stormo'', stationed in North Africa. However, pilots of this elite unit of the Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was abolis ...

opposed the adoption of the C.200, preferring the more manouvrable Fiat CR.42

The Fiat CR.42 ''Falco'' ("Falcon", plural: ''Falchi'') is a single-seat sesquiplane fighter developed and produced by Italian aircraft manufacturer Fiat Aviazione. It served primarily in the Italian in the 1930s and during the Second World ...

instead. Accordingly, the Macchis were then transferred to the 6th ''Gruppo'' of the 1st ''Stormo'' in Sicily, who were enthusiastic supporters of the new fighter, and to the 152nd ''Gruppo'' of the 54th ''Stormo'' in Vergiate

Vergiate is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Varese in the Italian region Lombardy, located about 45 km northwest of Milan and about 15 km southwest of Varese. As of 31 December 2018 it had a population of 8,716

Vergiate bo ...

. Further units received the type during peacetime, including the 153rd ''Gruppo'' and the 369th ''Squadriglia''.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 5–6.

When Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940, 144 C.200s were operational, only half of which were serviceable. The re-equipment programme, under which the type would have been widely adopted, took longer than expected; and several squadrons were still in the process of being reequipped with the C.200 at the outbreak of war.Cattaneo 1966, p. 6. Although the first 240 aircraft had been fitted with fully enclosed cockpits, the subsequent variants were provided with open cockpits at the request of the Italian pilots, who were familiar with the open cockpits that were commonplace amongst the old biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

s.

Service history

The C.200 played no role in Italy's brief action during theBattle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

. The first C.200s to make their combat debut were those of the 6th ''Gruppo Autonomo'' C.T. (''caccia terrestre'', or land-attack fighter) led by ''Tenente Colonnello'' (Wing Commander) Armando Francois. This squadron was based at the Sicilian airport of Catania Fontanarossa. A ''Saetta'' from this unit was the first C.200 to be lost in combat when, on 23 June 1940, 14 C.200s (eight from 88a ''Squadriglia'', five from 79a ''Squadriglia'' and one from 81a ''Squadriglia'') that were escorting 10 Savoia-Marchetti SM.79s from the 11th ''Stormo'' were intercepted by two Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

Developed private ...

s. Gladiator No.5519, piloted by Flight Lieutenant George Burges, jumped the bombers but was in turn attacked by a C.200 flown by ''Sergente Maggiore'' Lamberto Molinelli of 71a ''Squadriglia'' over the sea off Sliema

Sliema ( mt, Tas-Sliema ) is a town located on the northeast coast of Malta in the Districts of Malta#Northern Harbour District, Northern Harbour District. It is a major residential and commercial area and a centre for shopping, bars, dining, a ...

. The Macchi overshot four or five times the more agile Gladiator which eventually shot down the ''Saetta''.Cull and Galea 2008, pp. 46–47.

In September 1940, the C.200s of the 6th Gruppo conducted their first offensive operations in support of wider

In September 1940, the C.200s of the 6th Gruppo conducted their first offensive operations in support of wider Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

*Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinate ...

efforts against the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

island of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, escorting Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

dive-bombers. On 1 November 1940 the C.200s were credited with their first kill, a British Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

, on a reconnaissance mission, that was sighted and attacked just outside Augusta by a flight of ''Saettas'' on patrol.Caruana 1996, p. 166. With the arrival towards the end of December 1940 of X ''Fliegerkorps'' in Sicily, the C.200s were assigned escort duty for I/StG.1 and II/StG.2 Ju 87 bombers attacking Malta, as the ''Stukas'' did not have adequate fighter cover until the arrival of 7./JG26's Bf 109s.

Soon after, British air power in the theatre was enhanced, especially by the arrival of the Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

fighter, which forced a redeployment of Italian forces in response. Although considered to be inferior to the Hurricane in terms of speed, the C.200 had the advantage in terms of manoeuvrability, turn radius, and climb rate. According to aviation author Bill Gunston, the C.200 proved effective against the Hurricane, delivering outstanding dogfight performance without any vices.Gunston 1988, p. 255.

While the Hurricane was faster at sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

( vs the C.200's , the ''Saetta'' could reach more than at , although its speed dropped off at altitude: at and at with a maximum ceiling of . Comparative speeds of the Hurricane Mk I were at and at . Over and at very low levels, only the huge Vokes (anti-sand) air filter fitted to the "tropical" variants slowed the Hurricane Mk II to Macchi levels. Although the Macchi C.200 was more agile than the Hurricane, it carried a lighter armament than its British adversary.

On 6 February 1941, the 4th ''Stormo'' received C.200s from the 54th ''Stormo''. Once the autorotation problems had been resolved, the Macchis were regarded as "very good machines, fast, manoeuvrable and strong" by Italian pilots.Duma 2007, p. 188. After intense training, on 1 April 1941, the 10th ''Gruppo'' (4th ''Stormo'') moved to Ronchi dei Legionari

Ronchi dei Legionari ( Bisiacco: ; fur, Roncjis, sl, Ronke, german: Ronkis) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Gorizia in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy, about southwest of Gorizia and northwest of Trieste. It is the location of T ...

airport and started active service.Duma 2007, p. 190. The C.200 subsequently saw action over Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and the Balkans, frequently engaging in dogfights with British Gladiators and Hurricanes over the Balkans.

Yugoslavia

C.200s from the 4th ''Stormo'' took part in operations against Yugoslavia right from the start of hostilities.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 6–7. At dawn on 6 April 1941, four C.200s from 73a ''Squadriglia'' flew over

C.200s from the 4th ''Stormo'' took part in operations against Yugoslavia right from the start of hostilities.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 6–7. At dawn on 6 April 1941, four C.200s from 73a ''Squadriglia'' flew over Pola Pola or POLA may refer to:

People

*House of Pola, an Italian noble family

*Pola Alonso (1923–2004), Argentine actress

*Pola Brändle (born 1980), German artist and photographer

*Pola Gauguin (1883–1961), Danish painter

*Pola Gojawiczyńska (18 ...

harbour and attacked an oil tanker, setting it on fire. Due to limited air resistance being encountered, sorties flown by the type in this theatre were usually limited to escorting and strafing.Cattaneo 1966, p. 7.

The 4th ''Stormo'' flew its last mission against Yugoslavia on 14 April 1941: on that day, 20 C.200s from the 10th ''Gruppo'' flew up to south of Karlovac

Karlovac () is a city in central Croatia. According to the 2011 census, its population was 55,705.

Karlovac is the administrative centre of Karlovac County. The city is located on the Zagreb- Rijeka highway and railway line, south-west of Zagre ...

without meeting any enemy aircraft. Operations ended on 17 April. During those 11 days, the 4th ''Stormo'' did not lose a single C.200. Its pilots destroyed a total of 20 seaplanes and flying boats, while damaging a further 10. Additionally, they set on fire an oil tanker, a fuel truck, several other vehicles, and destroyed port installations.Duma 2007, pp. 190–193.

North Africa

Fitted with dust filters and designated ''C.200AS'', the ''Saetta'' saw extensive use inNorth Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, greater than any other theatre of war. The Macchi's introduction was not initially well received by pilots; in 1940, the first C.200 unit, the 4th ''Stormo'', replaced the type with the C.R.42. The first combat missions were flown as escorts for Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 bombers attacking Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

in June 1940, where one C.200 was claimed by a Gladiator. On 11 June 1940, second day of war for Italy, the C.200s of 79a ''Squadriglia'' encountered one of the Sea Gladiators that had been scrambled from Hal Far

HAL may refer to:

Aviation

* Halali Airport (IATA airport code: HAL) Halali, Oshikoto, Namibia

* Hawaiian Airlines (ICAO airline code: HAL)

* HAL Airport, Bangalore, India

* Hindustan Aeronautics Limited an Indian aerospace manufacturer of fight ...

, Malta. Flying Officer W. J. Wood claimed ''Tenente'' Giuseppe Pesola had been shot down, but the Italian pilot came back unscathed to his base.Malizia 2006, p. 28.

During April 1941, the C.200s of the 374th ''Squadriglia'' became the first unit to be stationed on the North African mainland. Further units, including the 153rd ''Gruppo'' and the 157th ''Gruppo'', were stationed on the mainland as Allied air power in the region increased in capability and numbers, including aircraft such as the Hurricane and the

During April 1941, the C.200s of the 374th ''Squadriglia'' became the first unit to be stationed on the North African mainland. Further units, including the 153rd ''Gruppo'' and the 157th ''Gruppo'', were stationed on the mainland as Allied air power in the region increased in capability and numbers, including aircraft such as the Hurricane and the P-40 Warhawk

The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk is an American single-engined, single-seat, all-metal fighter and ground-attack aircraft that first flew in 1938. The P-40 design was a modification of the previous Curtiss P-36 Hawk which reduced development time and ...

. According to Cattaneo, the C.200 performed well under the conditions of the desert climate, particularly due to its high structural strength and short takeoff run.

On 8 December 1941, Macchi C.200s of the 153rd ''Gruppo'' engaged Hurricanes from 94 Squadron. A dogfight developed, with the commanding officer, Squadron Leader Linnard, attempting to intercept a Macchi attacking a Hurricane. Both aircraft were making steep turns and losing height. But Linnard was too late, and the Macchi, turning inside the Hurricane, had already hit the Hurricane's cockpit area. The stricken aircraft turned over at a low level and dived into the ground, bursting into flames. Its pilot, the New Zealand-born RAF "ace" (six enemy aircraft destroyed and many more probably destroyed) Flight Lieutenant Owen Vincent Tracey was killed.

North African and Italian-based units were routinely rotated to relieve war-weary crews, aiding the resumption of an Axis offensive in the region during early 1942. During this offensive, which led to Italian and German forces reaching the outskirts of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, the C.200s were heavily engaged in bomber escort and low-altitude attack operations, while the newer C.202s performed high-altitude air cover duties.

In addition to interceptor duties, C.200s frequently operated as fighter-bombers against both land and naval objectives. The North African theatre was the first in which the type had been intentionally deployed as a fighter-bomber.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 7–8. During September 1942, the type was responsible for sinking the British destroyer , as well as several smaller motor vessels, near

In addition to interceptor duties, C.200s frequently operated as fighter-bombers against both land and naval objectives. The North African theatre was the first in which the type had been intentionally deployed as a fighter-bomber.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 7–8. During September 1942, the type was responsible for sinking the British destroyer , as well as several smaller motor vessels, near Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near th ...

, during Operation Agreement

Operation Agreement was a ground and amphibious operation carried out by British, Rhodesian and New Zealand forces on Axis-held Tobruk from 13 to 14 September 1942, during the Second World War. A Special Interrogation Group party, fluent in Ger ...

, an attempted amphibious assault by Allied forces.Cattaneo 1966, p. 8.

Following the decisive victory by Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

forces at El Alamein

El Alamein ( ar, العلمين, translit=al-ʿAlamayn, lit=the two flags, ) is a town in the northern Matrouh Governorate of Egypt. Located on the Arab's Gulf, Mediterranean Sea, it lies west of Alexandria and northwest of Cairo. , it had ...

, the C.200 provided cover for the retreating Axis forces, strafing advancing Allied columns and light vehicles. However, operations by the type in the theatre were curtailed around this time by increasing shortages of spares, fuel, and components; losses in the face of numerically superior Allied air power also played a role in the rapid decline of deployable C.200s. During January 1943, many Italian aerial units were withdrawn from North Africa, leaving only a single unit operating the type. Bomb-carrying C.200s were amongst those aircraft used during Axis attempts to resist the Allied occupation of the island of Pantelleria

Pantelleria (; Sicilian: ''Pantiddirìa'', Maltese: ''Pantellerija'' or ''Qawsra''), the ancient Cossyra or Cossura, is an Italian island and comune in the Strait of Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea, southwest of Sicily and east of the Tunis ...

. However, early 1943 marked the end of the C.200's viability as an effective front-line fighter.

Eastern Front

In August 1941, the Italian air force command dispatched a single air corps, formed from the ''22º Gruppo Autonomo Caccia Terrestre'' with four squadrons and 51 C.200s to the Eastern Front with theItalian Expeditionary Corps in Russia

During World War II, the Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia (''Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Russia'', or CSIR) was a corps-sized expeditionary unit of the ''Regio Esercito'' (Italian Army) that fought on the Eastern Front. In July 1942 the ...

; it was the first contribution of the Regia Aeronautica to the campaign.Neulen 2000, p. 60. By 12 August 1941, all 51 C.200s had arrived at Tudora, Ștefan Vodă, near Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

. On 13 August 1941, commanded by ''Maggiore'' Giovanni Borzoni and deployed in 359a, 362a, 369a, and 371a ''Squadriglia'' (Flights

Flight is the process by which an object moves without direct support from a surface.

Flight may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Flight'' (1929 film), an American adventure film

* ''Flight'' (2009 film), a South Korean d ...

). On 27 August 1941, C.200s carried out their first operations from Krivoi Rog

Kryvyi Rih ( uk, Криви́й Ріг , lit. "Curved Bend" or "Crooked Horn"), also known as Krivoy Rog (Russian: Кривой Рог) is the largest city in central Ukraine, the 7th most populous city in Ukraine and the 2nd largest by area. Kr ...

, achieving eight aerial victories over Soviet bombers and fighters.Neulen 2000, pp. 60–62.

For a short time, the 22nd ''Gruppo'' was subordinated to Luftwaffe V. Fliegerkorps.Neulen 2000, p. 62.

Subsequently, they took part in the September offensive on the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and B ...

; and as the offensive continued they operated sporadically from airstrips in Zaporozhye

Zaporizhzhia ( uk, Запоріжжя) or Zaporozhye (russian: Запорожье) is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper River. It is the administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia has a populatio ...

, Stalino

Donetsk ( , ; uk, Донецьк, translit=Donets'k ; russian: Донецк ), formerly known as Aleksandrovka, Yuzivka (or Hughesovka), Stalin and Stalino (see also: cities' alternative names), is an industrial city in eastern Ukraine loca ...

, Borvenkovo, Voroshilovgrad

Luhansk (, ; uk, Луганськ, ), also known as Lugansk (, ; russian: Луганск, ), is a city in what is internationally recognised as Ukraine, although it is administered by Russia as capital of the Luhansk People's Republic (LPR). A ...

, Makiivka

Makiivka ( uk, Макіївка, Makíyivka, ; russian: Макеевка, Makeyevka, ), formerly Dmytriivsk, is an industrial city in Donetsk Oblast in eastern Ukraine. Located from the capital Donetsk, the two cities are practically a conurbati ...

, Oblivskaja, Millerovo Millerovo (russian: Миллерово) is the name of several inhabited localities in Rostov Oblast, Russia.

;Urban localities

*Millerovo, Millerovsky District, Rostov Oblast, a town in Millerovsky District

;Rural localities

* Millerovo, Kuyby ...

, and their easternmost location, Kantemirovka

Kantemirovka (russian: Кантемировка; earlier Konstantinovka, russian: Константиновка) is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) in Kantemirovsky District of Voronezh Oblast, Russia. Population:

Founded in 18 cent ...

, moving to Zaporozhye

Zaporizhzhia ( uk, Запоріжжя) or Zaporozhye (russian: Запорожье) is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper River. It is the administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia has a populatio ...

late in October 1941.Cattaneo 1966, pp. 8–9.

Maintaining operations became increasingly difficult as winter took hold, the unit having not been furnished with the necessary equipment for conducting low-temperature operations; accordingly, flying was often impossible throughout November and December.Cattaneo 1966, p. 9. In December 1941, 371a ''Squadriglia'' was transferred to Stalino, but were replaced two days later by 359a with 11 C.200s. On 25 December, the C.200s flew low-level attacks against Soviet troops that had encircled the Black Shirt Legion ''Tagliamento'', at Novo Orlowka; and 359a ''Squadriglia'' intercepted Soviet fighters over Bulawa, shooting down five without loss to themselves. On 28 December, pilots of 359a claimed nine Soviet aircraft, including six Polikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 (russian: Поликарпов И-16) is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it was the world's first low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear to attain ope ...

fighters, in the Timofeyevka and Polskaya area, without loss.Neulen 2000, p. 62. According to Cattaneo, during the course of the three-day long 'Christmas battle', a total of 12 Soviet fighters were downed by C.200s with only a single friendly aircraft lost.

During February 1942, weather conditions had improved enough to allow for the resumption of full operations. From February onwards, the C.200 was employed in repeated attacks upon Soviet airfields at Liman, Luskotova, and Leninski Bomdardir. On 4 May 1942, the 22º ''Gruppo Autonomo Caccia Terrestre'' was withdrawn from active operation. The unit had flown 68 missions, taking part in 19 air combats and 11 ground attack missions. The 22º ''Gruppo'' was credited with 66 enemy destroyed, 16 probables, and 45 damaged and was awarded a ''Medaglia d'argento al valor militare'' (Silver Medal for military valor). The group was replaced by the newly formed 21º ''Gruppo Autonomo Caccia Terrestre'', composed of 356a, 361a, 382a, and 386a ''Squadriglia''. This unit, commanded by ''Maggiore'' Ettore Foschini, brought new C.202s and 18 new C.200 fighters. During the Second Battle of Kharkov

The Second Battle of Kharkov or Operation Fredericus was an Axis counter-offensive in the region around Kharkov against the Red Army Izium bridgehead offensive conducted 12–28 May 1942, on the Eastern Front during World War II. Its objectiv ...

(12–30 May) the Italians flew escort for the German bombers and reconnaissance aircraft.Neulen 2000, p. 63.

In May, the aircraft's pilots received praise from the commander of the German 17th Army, mostly for their daring and effective attacks in the Slavyansk area.Neulen 2000, pp. 63–64. During the German advance in summer 1942, the 21st ''Gruppo Autonomo C.T.'' transferred to Makiivka

Makiivka ( uk, Макіївка, Makíyivka, ; russian: Макеевка, Makeyevka, ), formerly Dmytriivsk, is an industrial city in Donetsk Oblast in eastern Ukraine. Located from the capital Donetsk, the two cities are practically a conurbati ...

airfield, and then to Voroshilovgrad

Luhansk (, ; uk, Луганськ, ), also known as Lugansk (, ; russian: Луганск, ), is a city in what is internationally recognised as Ukraine, although it is administered by Russia as capital of the Luhansk People's Republic (LPR). A ...

and Oblivskaya.

As time went on, the type was increasingly tasked to escort German aircraft. On 24 July 1942, the unit was shifted to Tatsinskaya Airfield

The Tatsinskaya Airfield was the main airfield used by the German Wehrmacht during the Battle of Stalingrad to supply the encircled 6th Army from outside.

Overview

The Tatsinskaya Airfield, 260 km west of Stalingrad, became the most imp ...

, with 24 ''Saettas''. Its main task was to provide escort for Stukas

The Orchestre Stukas (also referred to as the Stukas Boys, the Stukas or the Stukas of Zaire) was a congolese soukous band of the 1970s. It was based in Kinshasa, Zaire (now DR Congo). At the apex of their popularity, the Stukas were led by singe ...

in the Don Bend area, where there were few German fighters available. ''Hauptmann'' Friedrich Lang, ''Staffelkäpitan'' of 1./''StG'' 2 reported the Italian escort as "most disappointing". The Saettas proved unable to protect the Stukas from Soviet fighters.Bergström-Dikov-Antipov- 2006, p. 57. On 25 and 26 July 1942, five C.200s were lost in aerial combat.Neulen 2000, p. 64. After only three days of action from Tatsinskaya, one-third of the Italian fighters had been shot down.

The following winter, the Soviet counter-offensive resulted in the mass retreat of Axis forces. By early-December 1942, only 32 ''Saettas'' were still operating, along with 11 C.202s. However, during the first 18 months of its use on the Eastern front, together with C.202s, the C.200 had claimed an 88 to 15 victory/loss ratio, during which it had performed 1,983 escort missions, 2,557 offensive sweeps, 511 ground support sorties, and 1,310 strafing sorties.

Losses grew in the face of a more aggressive enemy flying newer aircraft. The last major action was on 17 January 1943: 25 C.200s strafed enemy troops in the Millerovo Millerovo (russian: Миллерово) is the name of several inhabited localities in Rostov Oblast, Russia.

;Urban localities

*Millerovo, Millerovsky District, Rostov Oblast, a town in Millerovsky District

;Rural localities

* Millerovo, Kuyby ...

area. The aviation of the ARMIR was withdrawn on 18 January, bringing 30 C.200 and nine C.202 fighters back to Italy and leaving 15 unserviceable aircraft behind. A total of 66 Italian aircraft had been lost on the Eastern Front – against, according to official figures, 88 victories claimed during 17 months of action in that theatre.Bergström 2007, p. 122.

A summary of the Italian expeditionary force operations included 2,557 offensive flights (of which 511 with bombs drops), 1,310 strafing attacks, and 1,938 escort missions, with the loss of 15 C.200s overall. The top-scoring unit was 362a ''Squadriglia'', commanded by ''Capitano'' Germano La Ferla, which claimed 30 Soviet aircraft shot down and 13 destroyed on the ground.de Marchi 1994, p. 8.

After the armistice

Following the signing of the armistice, which resulted in Italy's withdrawal from the Axis, only 33 C.200s remained serviceable. Shortly thereafter, 23 ''Saettas'' were transferred to Allied airfields in southern Italy, and flown for a short time by pilots of the Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force. In mid-1944, the C.200s of Southern Italy were transferred to the Leverano Fighter School. A lack of spare parts had made maintenance increasingly difficult, but the type continued to be used for advanced training until 1947. A small number of C.200s were also flown by the pro-German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

National Republican Air Force, based in northern Italy. The latter was only recorded as using the type for a training aircraft but using them for combat operations.

Specifications (Macchi C.200 early series)

Variants

The ''Saetta'' underwent very few modifications during its service life. Aside from the switch to an open canopy, later aircraft were fitted with an upgraded radio and an armoured seat. Some late-production ''Saettas'' were built with the MC.202 ''Serie'' VII wing, thus adding twoBreda-SAFAT machine gun

Breda-SAFAT (''Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche / Breda Meccanica Bresciana'' - ''Società Anonima Fabbrica Armi Torino'') was an Italian weapons manufacturer of the 1930s and 1940s that designed and produced a range of m ...

s to the armament. The four (including two proposed) C.200 derivatives were:

;M.C. 200 (prototypes)

:Two prototypes fitted with the Fiat A.74

The Fiat A.74 was a two-row, fourteen-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine produced in Italy in the 1930s as a powerplant for aircraft. It was used in some of Italy's most important aircraft of World War II.

Design and development

The A.74 marked ...

R.C.38 radial piston engine.

;M.C. 200

:Single-seat interceptor fighter, fighter-bomber aircraft. Production version.

;M.C.200bis

:Breda-proposed modification with a Piaggio P.XIX

The Piaggio P.XIX was an Italian aircraft engine produced by Piaggio Aerospace, Rinaldo Piaggio S.p.A. during World War II and used to power aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica.

Development

The engine was part of a line of 14-cylinder radial engines ...

R.C.45 engine producing at . Converted from an early production C.200. First flight 11 April 1942 from Milano-Bresso, flown by Luigi Acerbi. The aircraft was then fitted with a larger propeller and a revised engine cowling. Top speed in trials was . It did not enter production, as the C.200 had been replaced by more advanced designs.

;M.C.200AS

:Version adapted to North African Campaign.

;M.C.200CB

:Fighter-bomber version with of bombs or two external fuel tank

A fuel tank (also called a petrol tank or gas tank) is a safe container for flammable fluids. Though any storage tank for fuel may be so called, the term is typically applied to part of an engine system in which the fuel is stored and propel ...

s (as fighter escort).

;M.C.201

:As an answer to a 5 January 1938 request by the Regia Aeronautica for a C.200 replacement, Aermacchi proposed the C.201, which had a revised fuselage, an Isotta Fraschini

Isotta Fraschini () was an Italian luxury car manufacturer, also producing trucks, as well as engines for marine and aviation use. Founded in Milan, Italy, in 1900 by Cesare Isotta and the brothers Vincenzo, Antonio, and Oreste Fraschini, in 19 ...

Astro A.140RC.40 engine (licensed variant of the French Gnome-Rhone Mistral Major GR.14Krs) generating 870 cv (''cheval vapeur'', or metric horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are the ...

). But later the choice was for the Fiat A.76 R.C.40 engine with . Two prototypes were ordered. The first flew on 10 August 1940, with the less powerful A.74 engine.Sgarlato 2008, p. 19. Although Macchi estimated a top speed of , the prototype was cancelled after Fiat abandoned the troublesome A.76 engine.

Operators

; * ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' operated some captured aircraft.

;

* ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was abolis ...

''

* Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force

;

* Italian Air Force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march = (Ordinance March of the Air Force) by Alberto Di Miniello

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 28 March ...

operated some aircraft as trainers until 1947

See also

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* Bergström, Christer. ''Stalingrad – The Air Battle: 1942 through January 1943''. Hinckley UK: Midland, 2007. . * Bergström, Christer – Andrey Dikov – Vlad Antipov ''Black Cross Red Star – Air War over the Eastern Front Volume 3 – Everything for Stalingrad''. Hamilton MA, Eagle Editions, 2006. . * Bignozzi, Giorgio. ''Aerei d'Italia ''. Milan: Milano Edizioni E.C.A., 2000. * Brindley, John F. "Caproni Reggiane Re 2001 Falco II, Re 2002 Ariete & Re 2005 Sagittario." ''Aircraft in Profile Vol. 13''. Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications, 1973. . * Caruana, Richard J. ''Victory in the Air''. Malta: Modelaid International Publications, 1999. . * Cattaneo, Gianni. ''Aer. Macchi C.200 (Ali d'Italia no. 8)'' (in Italian/English). Torino, Italy: La Bancarella Aeronautica, 1997 (reprinted 2000). * Cattaneo, Gianni. ''The Macchi MC.200 (Aircraft in Profile number 64)''. London: Profile Publications, 1966. No ISBN. * Cull, Brian and Frederick Galea. ''Gladiators over Malta: The Story of Faith, Hope and Charity''. Malta: Wise Owl Publication, 2008. . * De Marchi, Italo and Pietro Tonizzo. ''Macchi MC. 200 / FIAT CR. 32'' . Modena, Italy: Edizioni Stem Mucchi, 1994. * Di Terlizzi, Maurizio. ''Macchi MC 200 Saetta, pt. 1 (Aviolibri Special 5)'' (in Italian/English). Rome: IBN Editore, 2001. * Di Terlizzi, Maurizio. ''Macchi MC 200 Saetta, pt. 2 (Aviolibri Special 9)'' (in Italian/English). Rome: IBN Editore, 2004. * Duma, Antonio. ''Quelli del Cavallino Rampante – Storia del 4o Stormo Caccia Francesco Baracca'' . Roma: Aeronautica Militare – Ufficio Storico, 2007. NO ISBN. * Ethell, Jeffrey L. ''Aerei della II Guerra Mondiale''. Milan: A. Vallardi/Collins Jane's, 1996. . * Ethell, Jeffrey L. ''Aircraft of World War II''. Glasgow: HarperCollins/Jane's, 1995. . * * Green, William. "The Macchi-Castoldi Series". ''Famous Fighters of the Second World War-2''. London, Macdonald, 1957 (reprinted 1962, 1975). . * Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. ''The Great Book of Fighters''. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. . * Gunston, Bill. ''The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II''. London: Salamander Books Limited, 1988. . * Lembo, Daniele. "I brutti Anatroccoli della Regia" . ''Aerei Nella Storia n.26'', December 2000. * Malizia, Nicola. ''Aermacchi, Bagliori di guerra (Macchi MC.200 – MC.202 – MC.205/V)'' . Rome, Italy: IBN Editore, 2006. * Marcon, Tullio. "Hurricane in Mediterraneo" . ''Storia Militare n. 80'', May 2000. * Mondey, David. ''The Hamlyn Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II''. London: Bounty Books, 2006. . * Munson, Kenneth. ''Fighters and Bombers of World War II''. London: Blandford Press, 1969, first edition 1960. . * Neulen, Hans Werner. ''In the Skies of Europe.'' Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2000. . * * Sgarlato, Nico. ''Aermacchi C.202 Folgore'' . Parma, Italy: Delta Editrice, 2008. * Spick, Mike. ''Allied Fighter Aces of World War II''. London: Greenhill Books, 1997. . {{Authority control 1930s Italian fighter aircraft Aircraft first flown in 1937 Low-wing aircraft C.200 Retractable conventional landing gear Single-engined tractor aircraft World War II Italian fighter aircraft